Sometimes television dramas get it wrong. And then there are times they miss the mark so spectacularly you wonder if they had a consultant on set or just decided on a quick Google search to not slow production down. The Rookie Season 4, Episode 17 (“Coding”) firmly plants itself in the latter category.

A young woman is injured in a motor vehicle collision, dies, and is declared dead on scene from a devastating abdominal injury. Nolan is asked by his firefighter girlfriend, Bailey, to check her driver’s license to see if she’s an organ donor. Check and check. Next cut is her arriving to the hospital with an honor walk already waiting and she’s taken directly to the OR for donation. The only problem? Medicine doesn’t quite work that way. Or at all.

The patient is shown being intubated (so far, so good), but the team isn’t performing compressions. Small problem– she has no pulse. For organs to be viable, blood needs to circulate. Without CPR maintaining blood flow, those organs are not viable for transplant.

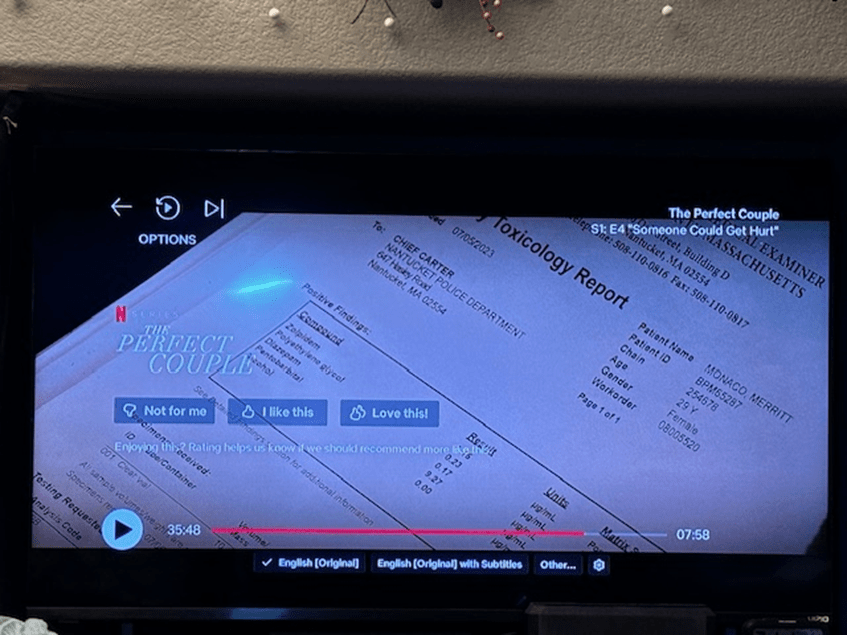

In TV land, organ donation is apparently as easy as checking a box on your driver’s license. In reality, donors undergo extensive testing—blood typing, infectious disease screening, toxicology, and so much more. It’s a lengthy, arduous process.

Yes, it’s television. Yes, we suspend disbelief. But medical inaccuracies like this reinforce misconceptions about organ donation. Families already face difficult decisions during an impossibly hard time. Feeding audiences the idea that hospitals snatch organs from people who just happen to check the donor box doesn’t do much to build trust in the system.

The ironic part? Organ donation stories can be powerful, emotional, and medically accurate. Real life has plenty of drama without rewriting basic physiology. You don’t need to sacrifice science to tell a compelling story.

Jordyn Says

Jordyn Says However, when it comes to medicine, historical might be considered a time frame of more than ten to twenty years ago because of the rapidly evolving nature of the practice of medicine. One example of this would be CPR guidelines. Did you know CPR guidelines generally change every five years? To put it simply, the way we are doing CPR now is not the way it looked even ten years ago. Often times, what a writer might consider a contemporary medical question is truly a historical one.

However, when it comes to medicine, historical might be considered a time frame of more than ten to twenty years ago because of the rapidly evolving nature of the practice of medicine. One example of this would be CPR guidelines. Did you know CPR guidelines generally change every five years? To put it simply, the way we are doing CPR now is not the way it looked even ten years ago. Often times, what a writer might consider a contemporary medical question is truly a historical one.